What is the nature of what is known to us? It’s difficult to remember, with any kind of clarity, what my trip was like. Most of my travels seem to happen to someone else: as soon as I leave my home my brain distances itself, a lack of object permanence applied to place. I forget, sometimes, that I was ever any place but right here, right now. Who can really conceptualize a different country, or a plane trip thirty-five thousand miles above the ocean? Context disappears. Only the effects remain. Recounting a journey becomes a narrative of disconnection: we did this, I saw this, I remember that. I love to tell people where I’ve been because traveling is the most interesting thing I’ve ever done, and I’m selfish in wanting to share that aspect of myself as an otherwise sedate English adjunct with cat hobbies and houseplant tips.

I was in Bratislava, Slovakia, once. I was with my teacher and three classmates, none of whom I knew well and aren’t in contact with today, which makes these memories mine more than ours. I stuck close to my friend Greg throughout. We were there on a short term study abroad trip in London and Vienna, the latter of which was close enough to Bratislava that it became “might as well” on the list even though we weren’t well prepared for the city. I say it flippantly, most of the time, to impress people who live in Missouri that I’ve been somewhere so exotic–oh yes, the castle resting on the Small Carpathian mountains, the ancient churches, the gelato, the blessing. That’s where I hurt my knee, let’s change the subject so I don’t bore you with the details. Let it remain more mysterious and lingering than the truth.

I know I’ve been there. The memory of that day feels like yellow paint and makes my cobblestone-weary feet ache.

We set out that morning from Vienna, June 13th, 2016. I dressed with purpose: freshly lanced and taped blisters encased in thick socks and tennis shoes, jean shorts, shirt, jacket, and a huge purse full of everything I could possibly need on a quick jaunt to another country. The strap felt reassuring against my chest, and my inner girl scout was satisfied. The hour long train ride between cities felt like a movie: unreal in a way that served as a defense mechanism against vulnerability. We were five Americans traveling from Austria, where most everyone’s second language was English, to Slovakia where we were lucky if one person’s third language was English. Even buying water was difficult with the language barriers, and it was painfully obvious that we were Americans, there more than anywhere else, when we opened our mouths. Silent, sitting or walking, we were just people on the street.

The train dropped us off at the wrong end of the city. We walked, passing houses with people we’d never know anything about, art we had practice judging after visiting the best museums in the world, and a protest that looked important but not recognizable beyond a crowd with signs opposing a gated, imposing building.

Our destination was Old Town, the ancient half of the city, which butted up against the Danube to the west, on the other side of which lay the newer part of Bratislava we wouldn’t have time to explore. We stuck to the cobblestone streets and centuries-old walls that blended from one storefront to the next. I had a wild thought that, if I approached the facade and pushed, the walls would fall domino-like and unreal from there to the river, revealing the lie of a city that claimed to be older than my country. The area is home to a host of historic monuments, ancient churches, political seats, and funny statues of men emerging from grates or leaning on benches.

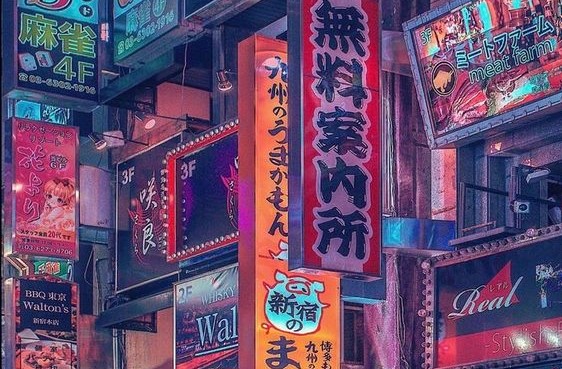

The homeless population was abundant, leftover remnants from the latest Syrian import. It smelled like trash in the way big cities got, coming and going among the vine covered churches and street art that looked like it came from the set of a black and white movie about doomed romance and wartime. The artfully crumbling facades of the wobbling buildings reminded us of the buckling weight of time–this part of the city had medieval roots alongside its baroque palaces and modern people.

From there we went walking, aimlessly exploring, wrenching our ankles back and forth on the uneven cobblestone. We walked around and found ourselves at St. Martin’s Cathedral which had been consecrated in 1452. Its gothic spire is a centerpiece of the Bratislavan cityscape. Greg found out that for a Euro you could go up to the treasury room which lay 26 huge stone steps up. We were graced to see a 17th century bible, an original Haydn mass, and a hoard of golden goblets. I don’t remember what any of them looked like, only that we saw them.

The city was layered complexly, walls turning into roads and highways below ancient ruins next to whole neighborhoods. We saw a castle on a hill and decided to find our way there, walking up, up, up a mountainside littered with cobbled streets and narrow, dangerous looking houses. We bumbled our way up to the Bratislava Castle monstrosity nestled into the small mountain range overlooking Old Town. One plateau was a park with oddly posed statues, high enough to start to overlook the city. Greg posed and we laughed, took a picture. We knew the view would only be more expansive the longer we hiked, though my knee was aching and I was dreading the descent.

I’ve never been able to relax on a trip like this. New places make me tense: unfamiliar people, new routines or lack thereof, constantly planning the way back home to safety. I’m often trapped in my head and feelings, not in the present moment, and I hate now to think of what I missed on that taxing ascent when I was more concerned about making it back down in one piece. That day was frustrating just in the fact I knew it would end quickly, and that I hadn’t done enough research beforehand. The opening of the world can be incredibly overwhelming to experience, and I shut things out instead of absorbing the experience.

We didn’t go into the castle as much as just turn our backs to it to take in views of the Danube and the city of Bratislava, St. Martin’s spire centered in the view. The distinction between old and new was obvious at that vantage point: one half bustling modern metropolis, the other a preserved relic from centuries past. We made the trek down sloping residential streets back to Old Town, then to another white-faced church at the edge of the square as a group, hustled along by our professor just as we’d done in a few ancient cathedrals in Vienna. This was much smaller, modest, and we ended up in a line being blessed by Franciscan monks who spoke no English but recognized wandering souls, clasping our hands one by one as we imagined what their life was like.

When I leaned on the plaster face of a monastery after receiving a blessing in another language, the wall was solid at my back, my legs shook. I imagined the stone foundations, the plaster, all of it extending down into the solid earth under the cobbled streets. Every street seemed to lead back to the fountain, a nerve center that radiated inward.

Main Square in Old Town, both translated names that fall flat to their reality, appeared between the narrow shop-filled streets like a meadow in the middle of a forest. Just off-center in the square stands a large stone fountain. It called to our tourist-tired feet, promising a solid place to sit around and contemplate among the gritty cobblestone streets that wanted repair. We used that great unmovable object as a base to meet up later and we split off into different directions.

I didn’t know the names of any locations until much later. The fountain in that square, called either the Roland Fountain or Maximilian Fountain, is a famous landmark. It was constructed under Maximilian II, a Holy Roman Emperor and the king of Royal Hungary, in 1572. Some say that Roland, a historic defender of the city’s rights, is the knight depicted at the top of the 35-foot tall column at the center of the fountain. Others believe it’s Maximilian himself. Legends have it that the knight or king still protects the city from his place above the fountain. The statue faces north, toward the town hall on one edge of the square, but a story goes that on midnight at New Year, he turns and bows in the direction of the older town hall, honoring people who had given their lives to save the city. There’s another rumor that he comes to life on Good Friday, waving his sword in all four directions to show the city is still under his protection, only seen by a true citizen of Bratislava, one with a pure heart who has never harmed another living soul.

I was unaware of the knight as I sat on the edge of the fountain and observed the area as my mind tried to catch up with my body. My priorities were more in line with simple delights than historic signifiers. I found blueberry gelato for a Euro at the edge of the square, a beautiful scoop of mottled purple in a cone. I have a picture of myself, incandescent, smiling and holding my cone beneath the sign reading Zmrzlina–ice cream in Slovak.

I was alone at that point, my fellow travelers darting off through different narrow streets, some revisiting the sheet music place we’d found, others buying more trinkets from little shops hidden in alleyways. I had my treasure safe in my bag: a tin mug with Bratislava written over colorful facades the city is full of and a ceramic magnet with a similar theme. Both for me, both beautiful, both having moved with me from home to home in the years since, a tiny piece of tourism and craftwork from halfway around the world, anchored back to the old city center.

As I sat on the stone rim of the fountain, watching my friends flit in and out of view and savoring my cold treat, I remember a profound feeling of distance. Bratislava was the furthest I’d ever been from home, and my time there felt like the last stretch of a rubber band pushing closer and closer to its own snap. Birds descended to fill in the space of the mostly empty square, pecking at crumbs left behind from trailing tourists like myself. There was a larger shop filled with odds and ends on the only corner I hadn’t explored, and I wanted to go in. Greg had already spotted it and was lost behind the doors and clutter before I could remark on it. I was struck still with exhaustion and pain in accompaniment with the thud of my brain, processing, tied inexorably to the beating stone heart beneath my feet. Old Town was alive, an ancient stone beast that allowed us gently to walk on its back.

I never got up the energy to go to the little store, and by then we had to find our way back to the train station on the other end of town. It involved fumbling with a ticket machine that none of the locals seemed bothered with, our professor using crude charades to communicate with the others in line. We caught the tram back to the train station and left Bratislava. Another hour, mostly of us dozing, and we were back in Vienna where everything was closed, hungry with no restaurants to feed us, to catch a tram, walk most of a mile and end up back at the hotel. We’d visit Schonbrunn Palace the next day, then start our 35 hour journey back home.

My trip is real only in flashes of conversation, half sentences and fleeting impressions just like the day in Bratislava left on me. Distance makes memories fuzzy, time more so. If places exist in how we remember them, Bratislava exists only in my mind. The places I visited there might as well be figments of imagination, only concrete in a handful of pictures and a journal entry hastily written half-asleep that night. It’ll never be real again. Some places you can’t go back to; even if I made it to Slovakia again one day it would be a whole new world, a whole new me. It makes me wonder if it matters that I’ve gone and done and seen–nothing about my trip affected anything else. The trains still would’ve run on time, the souvenirs bought by some other tourist, the sights seen by thousands, a city of half a million living out their days unaffected. My existential despair is lifted at the thought of some butterfly effect I may have had, then amplified at the concept of fate and the long stretch of history dictating that I am insignificant.

I can’t say what it means to have gone, done, seen. What does that mean when you don’t have anything to show for it, aside from offhand comments and a broader sense of the vastness of the human experience? We always have to turn back, go home, and I have to wonder: is it about the going, or about having gone?