This is an extract from a longer poem still in progress, ‘The Tipping Line’, written to the son of my friends Ken and Jane Vickers. Rowan studied drama at Julliard and is now acting professionally in New York. Earlier sections of the poem reference WWI veteran James Whale who found fame in 1928 directing R C Sherriff’s WWI drama, Journey’s End, and who went on to Hollywood to direct iconic films such as Frankenstein, The Invisible Man and Showboat. The Creature referred to here is Frankenstein’s monster.

UNIT 4

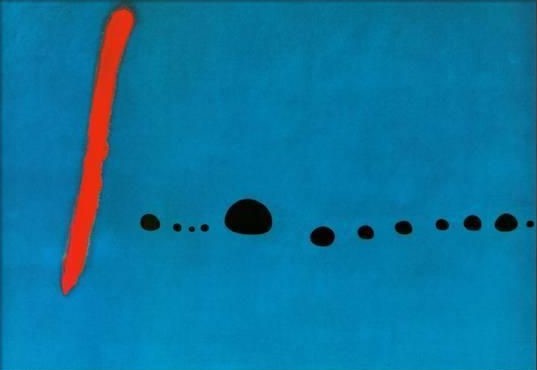

I instructed him, during the clear sky,

something about the heavens.

Dear Rowan,

As you know, I’m teaching at Leeds University.

It’s a one semester gig. The offer will be

repeated and I’ll accept another two

but this is the first—a few years after your father

has beaten his cancer and before mine dies.

Then, in three years time you’ll read a poem

at his funeral in Bermuda, your mother

holding tight my hand. But tonight

I’m grading students’ portfolios in my office.

It’s late and I’m avoiding the hell of my flat

rented, crazily, sight unseen

in the centre of the student ghetto.

Its “well appointed” kitchen / dining-room /

living-room opens onto an alley

between red-brick houses, where maids might once

have chatted over laundry duties and man servants

might have polished cars. But now it’s nightly

re-strewn in ritual fashion with overturned bins,

pizza boxes and vomited Chinese take-away.

What thrives out there is stench and slick and shadow –

and buddleia, the roots sucking deep from improbable

footholds. And on the wall of the house at the end

of the alley, some student, as only a student would,

has taken the time to spray-paint the head of Creature

as designed by Whale and rendered in purple.

The image is small, the size of a clenched fist.

And in a Leeds neighbourhood where no-one

lingers for long, and as only a student might worship

a rebel, the gaze of our Creature is daring and splendid,

as if he clings to a noble ideal—as if,

like a true radical, he has contempt

for those who judge him, daring the righteous to hunt

his corrupting flesh: Light them, he sneers. Go!

Go and light your torches! He’s Jimmy Dean,

Malcolm X, and Che Guevera.

And here,

in a back alley, as if Creature and creatures,

students adopt his gaze and haul themselves

from gutters to stomp and dance and think they have

the answers. Not yet! The night is ours,they scream,

not yours. Not yet! They sway and trash cans tumble.

And just listen to them; listen to them howl.

Join them Rowan and you’ll be all the richer.

And me? I play the part of the Mad Professor

who bangs on his ceiling and scowls on the rare occasion

he meets his neighbours in the corner shop.

The all-night party in the flat upstairs

is why I’ve decamped to the office to grade these papers.

I’ve been expecting much in the way of students’

distopian visions, eating disorders, betrayal

by parents or partners, OCD behaviours.

I’m not disappointed but will also receive

a screenplay about a Japanese man who saved

the Akita from extinction, poems that employ

the vernacular of Yorkshire’s mining fraternities,

prose inspired by Leonid Andreev’s photographs

of his pre-revolution Russian middle-class family,

and I’ll read these lines by young Thomas Ellison:

The Glade

is a gleam of light there

is a bright space between

the clouds like frith in fir lap up the golden fish […]

And I’ll be made young again, electrified

by a student’s daring. And I’ll go on

to read and reread stories by James Thurley

and Joshua Byworth that make me weep because

their writing is exquisite and because their worlds

begin and end in the fantastical way

that students conjure best and because, Rowan,

I’ll never again be all the younger.

Some of the best work grew from encounters

in the Brotherton Library’s Special Collections,

brought to life by Sarah Prescott, who explores

marvels preserved under glass and on shelves.

Included in her talks are artefacts

stored in the Liddle Collection, which conserves

detritus and records from the First World War:

a sardine tin that kept safe a map of Bavaria;

a German pilot’s Teddy-bear mascot; a bible

that once protected Private Salisbury’s heart

in Gallipoli, the shrapnel lodged therein;

panoramas of Turkish landscapes photographed

by Air Force balloonists; a Huntley & Palmers biscuit

never eaten despite starvation conditions,

and a lady’s broach, believed to be made from the thigh bone

of Sergeant Thomas Kitching and presented

to his sweetheart, Lizzie, who in return sent twelve

embroidered postcards to the front.

In each

of the three years that Sarah delivers her talk,

so moved are several students they explore

the Liddle Collection further, in their own time.

Samantha Gooch retrieved this from a file

belonging to B H Pain, a Lieutenant Surgeon

who served in Gallipoli, and who thought to save

this report in the Evening Standard:

He is lying on barbed wire looking more like a bunch of wet rags than a man, and every time he tries to tear himself away, crimson stains ooze through his soaked uniform. A comrade struggles to free him. He, too, is shot down. And they lie together in the cruel mesh nodding feebly to one another. The machine guns sieve their broken bodies and the rising sun crispens the blood and sea water in their khaki. Their eyes roll back on the Oriental sky to see a beautiful mirage of factory chimneys, chip shops and cobbled streets slushed with rain.

I imagine Samantha was struck by the tender account

of these protracted deaths. In response,

she writes the last moments of Private Potts

in this Turkish no-man’s land and has her witness

to the scene implore of the baking soldier

“Potts, wait out the sun.” And hear the Creature

howl Not yet. Not yet.

When I explore the Liddle for connections

to Bermuda, Sherrif and Whale, I find

John Wilfred Staddon, born March 20th,

1889, a civil engineer

of 58 Brook St., Luton, who served

in the East Surrey Regiment, 12th Battalion,

C Company, promoted to 2nd Lieutenant

then to Lieutenant. And in the Company Roll Book

Staddon notes that he is fighting alongside

a groom, two cooks, a chemist, a clerk, a carman,

a barman, a tinman, a packer, a painter, a printer,

a plumber’s mate, a sugar boiler, a leather dresser,

a lift attendant, a sign writer, a carpenter, a gardener,

a labourer, a chimney sweep, a crane driver,

a machine minder, a counter hand, a retort setter,

a stoker, a bricklayer, a milkman, a housekeeper,

a glass blower, and a motor driver who Staddon records as

14296

Private Collins, W.H.

of 13 Old Road, Rotherhithe.

He enlists on the 10th of November 1915.

He enlisted aged 23 and 7 months.

He is a married member of the Church of England.

He possesses a musketry classification of 54.

His rifle number is 3546.

His headdress measures 6 & 7/8ths

He wears size-8 boots.

And of the 53 men in Company C

24 are wounded and it’s recorded

Private Collins Died of wounds.

And tucked within Staddon’s file is a ragged

Time Table for Attack, saved from the trenches

by the Lieutenant and sometime later Sellotaped

on the reverse to protect the folds. It details

the forward advance expected of Company C

during a morning offensive at the Somme.

I rest it on the stand designed to aid

the examination of precious documents.

It is a sorry thing, splattered with mud

from the trenches, the typewriter ink dissolving.

What strikes you, added by the commanding officer,

is the precision to minutes that men were to reach

their positions during battle.

And almost

overlooked within Staddon’s papers

is a scrap of a manila envelope on which I discover

this handwritten note:

The rusty stains on the Time Table of Attack are the blood of my commander whose runner found me amidst all the ‘shot of shell’ on the run up to Flers. He too did not survive.

I am holding a document splattered not with mud

but with a man’s blood, shed one hundred

years ago in a ‘shot of shell’. .

It is something Homer might have built

a scene upon. And I imagine this

is something Staddon knew and it is why

he saved the orders. And I imagine this:

that when he tucked the orders safely somewhere

on his person in that field of battle

he was weeping. And I imagine Staddon

was a good man.

* * * *

I left the research there that day and walked

home through Leeds’ Cemetery Park, a place

where centuries of graves were bulldozed under

so students might sit on blankets in the sun.

The deconsecrated chapel at its centre

is surrounded by disused headstones that now serve

as flagstones, and the chapel houses a kingdom

of lesser, mouldering files, too vast to store

in the Brotherton Library’s Special Collections.

In the morning, while all Creatures sleep,

I Google “John Wilfred Staddon” and nothing

is returned. But when I go back to the Brotherton

later that day I discover this:

Staddon served alongside R. C. Sherriff

demobbing soldiers at the end of the war.

There’s a sketch of Staddon in the file,

drawn by Sherriff, and an interview,

in which Staddon says of the famous playwright:

I instructed him, during the clear sky, something about the heavens. He was very interested in astronomy.

After the war I went down to his house after meeting him in his insurance office and he took me on the river.

I lost touch with him very much. I did correspond to some extent but I met him at Morley College only 100 yards or so from where I am now and he gave a lecture. I think it was on play writing.

I spoke to him afterwards. I said: “You remember your colleague?” He had no recollection of me at all.

I didn’t press the point but thought that there might be plenty of people who might try to cash in on the fact that he was an important man.

I left it at that but he must have known me because I pointed out who I was.

A captain, wounded at Passchendaele

and awarded the Victoria Cross, once stood

in a dark foreign field on a clear night

and was instructed by a fellow soldier

on the relationships of stars in their heavens—

but he then went on to find celebrity

and to forget such men and incidents.

And so Sherriff’s better is denied his past

and his meagre postscript. And both their worlds

and we are all the poorer.

When I returned

to the flat, I ate my takeaway

and listened to your granddad’s strange recording

with La Diva Sutherland – which does not please

the upstairs neighbours. Then I photographed

our graffitied Creature, to prove the image

wasn’t (isn’t) mere invention.

Alone in that darkening alley I remember

you once played the Creature in Bermuda.

Your father loaded the DVD

(I’ve yet to see you live on stage)

and my old friend and I

watched his son transform

into a nightmare resurrection—

stitches incised across your cranium

down the forehead to the chin and neck,

producing one head from two halves.

And in front of Bermuda’s corrupted doctor,

the politician soon to be hounded by his villagers,

you made flesh our ills and screamed

that here before you is the proof that they exist

because I am, I am, I am, I am!

And believe me when I tell you

that tonight in Leeds, a multitude of acolytes

will pass beneath the Creature

intent on underscoring their existence:

young men in muscle T-shirts,

both the sexes in their skinny jeans,

cupped palms guarding lights for cigarettes,

bottles hurled with purpose to electrify the night.

And they will stumble, raise themselves

from gutters, and be unconcerned about the stars.

But a few will retreat at dawn

and bleary eyed will read

of men like Staddon and be moved.

I have the proof before me:

This is the work of a student who has read the file on Arthur Addams-Williams, killed at Sulva in 1915 while leading his company at Chocolate Hill. So moved is Kevin Gregario he imagines the letter to Addams-Williams’ mother informing her of how her son had died – and, most eloquently, he writes the incidents she never can be told.

Kevin has returned to America

and like you has found a woman he loves.

He wants to be a teacher and I wish him well.

And I like to imagine he’ll one day see you in a play

and be moved to come backstage.

And I like to imagine you will greet him, Rowan,

and will put aside celebrity to talk a while

of his time in Leeds and of clouds like frith in fir

and something of stars in their heavens.