“The fate of the emigrant: a foreign country cannot become a homeland. Yet the homeland becomes a foreign country.”

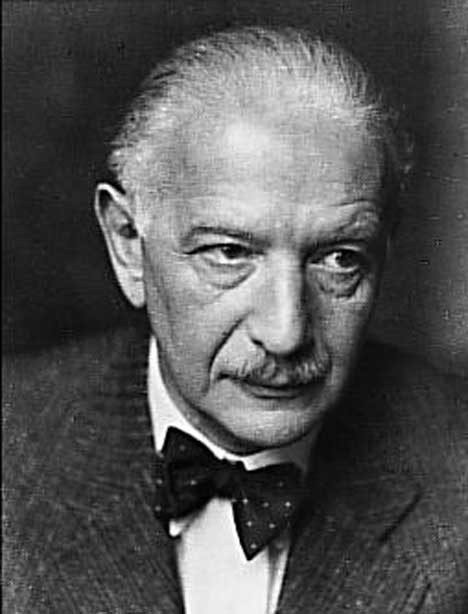

Born in Vienna in the latter part of the 19th century, the critic and essayist Alfred Polgar died in a Zurich hotel room in 1955. Exiled by Hitler’s rise to power, and only relatively recently returned to Europe, he had lived to see the vanishing of the Habsburg and Weimer worlds whose newspapers and journals had seen the first publication of his works.

In America he wrote about the fate of the emigrant: someone who, even if they died “in a regular bed from a regular illness”, could never die a natural death. He hears someone speaking to an acquaintance who has had the good fortune to be able to emigrate to Australia. “My God that’s far” the man says. The tragedy of exile is summed up in the three word response: “Far from where?”

It is difficult to approach his writing now without a sense of the loss he suffered – like so many others – in his American exile. He wrote a sharp, aphoristic German, whose style emerged from the coffee houses of Vienna. His subjects include many incidental details of his life in Vienna and Berlin. Theatre reviews from both cities were a staple of his writing. There’s a great deal now in his subject matter that seems lost in another time and place. Perhaps for this reason there has been no English translation of his selected writings. Yet his writing remains compelling. To approach his work even with a halting understanding of German, is to be drawn into an attempt – dictionary in hand – to get closer to the words he wrote and his sense of the world he lived in.

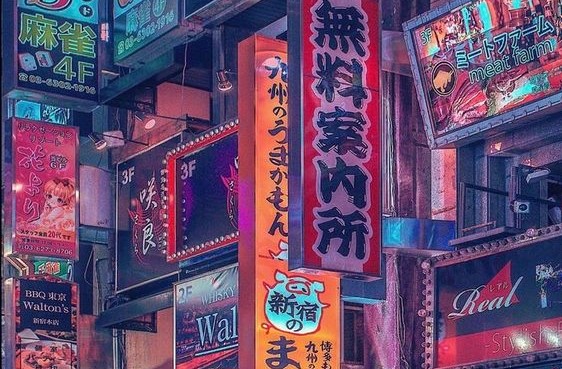

His style is immediately engaging. The style of a writer who wants – is fated perhaps – to be completely individual. In his ‘Theory of the Cafe Central’ he explains that the Cafe Central, one of the writers’ cafes in Habsburg Vienna,

“… lies on the meridian of solitude, at the very particular latitude of Vienna. Its occupants are for the most part people whose enmity to humanity as a whole is only equalled by their desire to be with people who, like them, wish only to be alone, but require company to realise that wish”.

The cafe steps in as a substitute solution for people who have no sense of belonging to family, work or party. “It is a place for people who know their own desire to leave and be left, but do not have the nerve to live up to that desire. It is an asylum for people that must kill time, in order not to be killed by time.”

Polgar shared this individualism. But the individualism of the cafe was, of course, anything but healthy or robust. “Here powerlessness develops its own peculiar strength, the unfruitful bears fruit, and lack of property pays interest.” These outcasts from wider society are uneasy, helpless, and, it goes without saying, more than a little decadent. The cafe represents in its way “a kind of organisation of the disorganised.”

By 1926 though, when the essay on the Cafe Central was published, Polgar had distanced himself from a cafe culture that had tended always to look inward, interested only in itself. The fascination with personality this necessarily involved was not enough. The world of the cafe was too narrow. “The Centralist” he writes “lives parasitically on the anecdote that revolves around himself.”

“The fish in the aquarium like to live, I think, like the regulars in [the Cafe Central], moving around each other in narrow circles, with no particular goal in mind, using the oblique refraction of their medium for their various amusements, always full of expectation, but also filled with concern, that one day something new might fall into the glass bowl. They continue to play ‘sea’ with serious faces on their artificial miniature sea floor, and would be completely lost if, God preserve us, the aquarium were turned into a bank.”

In one of the aphorisms he collected, Polgar goes further, suggesting that to cultivate personality is to “use weakness of character to compensate for lack of talent.”

Polgar had begun writing in the context of the Viennese feuilletion: light, ironic, review and opinion columns written for entertainment. The reader slides to the end of such columns, he suggests, in a brief reflection on the form, with no particular idea how he or she got there. The essays Polgar published in the 1920s and 1930s start, in contrast, from the given, from the world around him; above all, from a feeling for the people, places and events he is writing about. The conversational tone and aphoristic brevity of his short pieces are also reflections of his desire to connect directly with a wide public, whether in newspapers or the increasingly popular collections of his writings published in the 20s and 30s. He wants to be quotable and commercial. Rilke – another child of the Habsburg empire – once grandly proclaimed to his poetic self, that “for you, everything was a commission”. For Polgar, everything was a commission.

Another essay of 1926, ‘I cannot read novels’, reflects obliquely, if perhaps disingenuously, on his sense that his concern should only be with real, not imagined worlds. There are already too many people in the world he writes, at least they should all be granted sufficient bread, air and space. Yet people are inevitably bound to one another by ties of curiosity, sympathy and necessity, however much an individual’s capacity for sympathy might fail. The things of neighbouring people fill up around you “the way junk mail constantly fills your table”. If that is the case, why allow only imaginary lives and imaginary sufferings to fill your consciousness?

“How can one only read novels? That’s to carry water to the sea, sand to the desert, tradition to the royal theatre … winds to Vienna, esprit to Prague, owls to ruined castles, Greeks to Athens, boredom to literary journals …”

There’s as aside in the essay though, which also reflects his deepening understanding of the way his personal individualism was threatened by the mass movements of his time. Providing the people with enough bread, air and space really is a problem. Communism he says in passing,

“claims to have a solution, but although its theory is compelling and practice very seductive, I have a terrible fear of it. Not because it would take away my property – my factories and my villas – it can have all of those, with my bank deposit thrown in, but because it so cruelly narrows the possibilities of privacy. It shoehorns the individual into the mass: to be menaced, Moloch-like, by the unsprung jaws of collectivism. I cannot understand why people who are horrified by the thought of being buried in a mass grave, that’s to say, in all too narrow contact with each other, scarcely shudder to live side by side with others in a mass, their work or their pleasure lumped together …”

It was Fascism though which menaced Polgar’s life more closely. Many of the short pieces of the 1930s, however light and conversational their opening, become reflections on the violence and the impending violence of the times. The essays become reminders and warnings of political reality. A few paragraphs on ‘Culture’ written during this time describe a small deserted settlement (Arcegno) whose inhabitants have emigrated to America. A single streetlamp which hangs from a wire across the deserted main street is, he suggests, an image of culture. Its role now is “to show with its enchanted light, how disenchanted, sad, and god-forsaken the surrounding world has become.”

Throughout his life, Polgar was aware of the limitations of culture. One of his last pieces, written after his return to Europe, hauntingly combines a sense of those limits with an image of the isolated, dislocated intellectual.

In ‘Dilemma with books’ he describes a visit to an old friend, Henderle, a literary historian. Henderle now lives in a single, shabby hotel room – he cannot afford the cleaning charge. He is opening a parcel of books his old publisher has sent him, and describes his dilemma with books. Often on their account, he says

“I have had to make abrupt departures. History, you might say, has me on the run. What books I have, I always leave behind. But wherever I find a new resting place, there they begin to gather again. And every time I’ve gathered so many, that it begins to look like a library in embryo, my sanctuary is blown apart and I need to be on the move again.”

The books he is sent are always noteworthy. But where to put them?

“He points to the window ledge, loaded with books, ‘and there’s another pile up there’, he says, that being the top of the wardrobe, ‘and under the sink … for the most part books I shall no doubt never look at again. What shall I do with them? If I had a good stove, I’d know what to do’”.

He hasn’t changed his attachment to books, but now:

“I see them above all as objects. As things with a particular weight; things that take up space, and must be stuffed from time to time into a trunk and never taken out. It’s the solidity of books that oppresses me. That’s the crux!”

The culture business goes on. He receives books from publishers, review copies from newspapers, publications from former students. But what use are they, aside from the reference books that might aid his failing memory? “They have me” Henderle says. “I don’t have them”.

“But still you’d like something to read, no? So I buy something from time to time from the second-hand book shops. A crime twice over, in view of the problems I have both of space and money … to find a good way of disposing of books is a difficult problem. I’d like to know how one does that.”

“But you can’t do it”, Polgar suggests “a small part you belongs to each one. Why not give them away?”

“’To whom?” [Henderle replies] “I don’t have dealing with that many people here, and it’s only a superficial acquaintance. I only really know the hotel manager. But he only reads the newspaper, the sports pages at that. Old neckties are closer to his heart than new books. Sometimes I contrive to forget one and I leave it on the tram. Or on a bench in the park. The park’s better. A despicable business, no? I’m always left a little downhearted by it. As if I’d committed a sin against the spirit, even if there’s nothing much to occupy me in the book. As if I’d been unfair somehow to the author. But I console myself with the thought that someone will pick up the innocent foundling, and the book will find a more congenial home that it did with me.”

There’s a pile of recent books on a chair that the doctor would take for the hospital. But he can’t be given them – they have handwritten dedications. Perhaps the page could be torn out, except the author has been careless enough to write on the title page. In any case, that would be to respond to a courtesy with an insult (and dedications are often hard to write). Polgar concludes:

“I said my farewells, and Henderle said that he’d be going out too – to the park. He hesitated a while at the door, then went back to the window ledge and returned with a book held tightly under his arm. He seemed a little distracted.

I had in my bag the copy of my new book I’d meant to give him, complete with its handwritten dedication. I left it where it was. At that moment there was nothing more I could do for the man.”