“Should we be here?” she asked.

“Why not?” he said. “We’ve as much right as any.”

“But they’re locking up,” she said. “I can hear them. I can hear their keys.”

“Good!” he said.

“What do you mean ‘Good’?” she said.

“Let them!” he said.

“But how will we get home?” she asked.

“In the car,” he said.

“But we came on the bus… and the train. What do you mean? We have no car,” she said.

“So what is this?” he said.

“Are you crazy?” she said. “That’s Lenin’s car.”

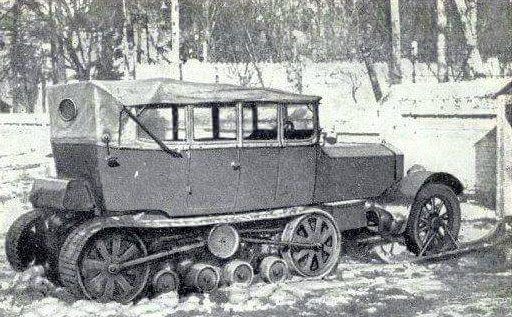

“Well he’s no need of it now,” he said. “Not where he is. Anyway it’s not a car. It’s his Ghost… his Rolls-Royce Silver Ghost.”

“You’re being stupid,” she said. “Let’s go. I want to go,” she said.

She made to turn. He kept hold of her hand.

They heard voices, somewhere outside. Her fingers tightened in his, then slackened, like the kneading claw of a cat, as the voices moved away.

“They’ll kill you!” she said.

“Have to catch me first,” he said.

“It’s ancient. It will never run,” she said.

“Then we’ll – I’ll – push it,” he said. “It has skis, doesn’t it? Look! The only Rolls-Royce in the world with skis, and tank tracks. It was made for us.”

He moved towards it. She pulled him back.

“It was made for Lenin,” she said.

He let go of her hand, stepped over the rope.

“I’m frightened,” she said.

“Don’t be,” he said.

“So help me God, you’re wicked,” she said.

“That’s why you love me,” he said, not looking at her but at the Flying Lady on the front of the Ghost.

He moved to the door, held the handle… which was cold. “Just think whose hands have been here,” he said. “Lenin… Stalin…” He tugged at the door.

“What are you doing?” she said.

The door came open, sagged on its hinges, like the cover of an old book.

“I don’t believe you!” she said. “I want to go home.”

“Let’s!” he said, reaching to her over the rope.

“This is madness!” she said.

“If it was good for Lenin, it’s good for the workers,” he said.

“You are a student,” she said.

“Of engineering. That’s nearly working. Come,” he said.

“We mustn’t,” she said, stepping to him over the rope. “Seriously. Someone will hear. Someone will come.”

He held the door for her. “Get in… please,” he said.

She slid across the leather, smoothed her coat under her with her hands.

“Will it start? It will never start,” she said.

“Shall I try?” he said.

“No,” she said. “I can’t believe we’re doing this. To think: Lenin sat here…”

“In the back, actually,” he said. “I’ve seen a photograph.”

“Give it a little try,” she said, not listening to him.

“Are you sure?” he said.

“Yes,” she said. “I know it won’t work. Not after all this time. But… try,” she said. “Just once.”

She watched him through the windscreen. He lifted the side of the lead-coloured bonnet. It rose stiffly, like some ancient eagle’s wing. She was thinking how it smelled in there: a dry, woody, dusty smell, like a cobwebbed dacha unvisited for years.

“How come you know all this?” she called to him.

“I didn’t come all the way here just to look at his curtains and bath,” he said.

He got in beside her, fiddled with levers, turned knobs, watched the steering wheel, which he held tightly.

Nothing happened.

“It won’t start,” he said. He sighed. “Perhaps you’re right. Perhaps we should go.”

“Maybe you did something wrong,” she said. “Try it again. Just once.”

He repeated his drill: flicking, twisting and pushing, as if operating some great musical organ. He gripped the wheel. Her fingers held the edge of her seat.

Deep inside the car, so deep it seemed to come from some dark and unreachable cavern, something stirred.

First there came a groan, then a tremor, then a shudder. The old car rattled, shook. They jounced in their seats. And then… nothing.

It was as if a bear had thought of waking, had even opened one eye, yawned… and then gone back to sleep.

“Try it again,” she said, putting her hand on his arm, whispering, wanting and yet not wanting to rouse the bear.

The Ghost groaned and shuddered as before, but this time it groaned and shuddered again… and again, till the shudders subsided and the car was running… actually running… at their hands and at their feet.

“I’ll open the doors,” she said, getting out.

“Are you sure?” he called after her.

She was already unbolting the exit: suddenly, against her face, the cold shroud of the late afternoon.

He held the wheel. The car lurched to the grey light.

She jumped in.

The Ghost climbed the track at the back of the mansion in the otherwise still and snow-covered park.

“Let me drive,” she said as they went out of the gates.

“You don’t know how to,” he said.

“But I can ski. This has skis,” she said.

She pressed against him, put her (now gloved) hands on the wheel. He shifted, let go.

Lenin’s lemon-painted mansion disappeared in the trees behind them.

They did not take the roads home, but instead drove over the plains and through the forests, the great headlamps of the Ghost glowing through the birches and the pines. As they crossed the quiet, snow-filled land, Yelena felt as if she were the Ghost’s Flying Lady.

When they reached Moscow they did not go home. Instead they parted the crowds outside Red Square and entered its vastness through Resurrection Gate.

Choral singing came faintly from the small Cathedral of Our Lady of Kazan in one corner.

They circled the pyramid of Lenin’s mausoleum – lap after lap, so it seemed to them – amid falling snowflakes in the closing dark.

And they drove like that, the lights of the Ghost flaring golden on the walls of the Kremlin, until they and their laughter were stopped.

THE END