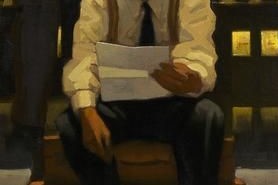

The letter lay unopened on the kitchen table for nearly a week before the old man finally succumbed to his curiosity. It had been tucked innocently between the telephone bill and an ad pamphlet, marked with a decorative floral stamp and neatly hand-addressed—only not to him. His home’s address was indeed written below the name, but this was clearly a mistake. Even so, he could not bring himself to throw it away—it was another person’s possession which fate, in conjunction with the US Postal Service, had entrusted to his care. The letter was simply not his to dispose of.

The old man wondered about Ariana Tyler, the intended recipient who was not him, and Mia Marsh, who had mistakenly sent the letter to his address. He felt the presence of these strangers in his kitchen every time he walked past the misdelivered letter, lying innocuous and prim in its white envelope in the middle of the table. Eventually, he had grown so accustomed to the company of these faceless women that he felt they wouldn’t mind his reading it. He carefully sliced open the envelope with his late wife’s monogrammed letter opener and removed the tri-folded sheet of loose leaf.

Dear Ari, he read, with methodical concentration, carefully picking the shapes of the alphabet out of the unfamiliar handwriting, carving a path of understanding through the English words, I hope this letter finds you well! How was the rest of your summer? I spent most of mine at home. It was nice to spend time with my family, especially my brother, since as you know I was pretty homesick in Oklahoma. I also spent a weekend at the beach with my high school friends, which was nice but a little strange, since we used to have practically everything in common but now we all have friends and stories and places that we don’t all know.

I’m back at school now; classes have started but the workload hasn’t really hit me yet (which is great since I have plenty of time to write to you!). My new roommate is nice and pretty quiet, but it’s weird not living with my friends from last year. I have a lot more time to myself, which I think will ultimately prove a good thing, especially once I have a lot of work, though right now I’m just spending a lot of time just reading and listening to music. Speaking of which, what was the name of that band you showed me? I forgot to write down the name but I really liked their stuff.

Oklahoma seems so far away now. It was less than a month ago, but I settled so easily into life at home and now life at school that it seems crazy to think that only a few weeks ago we were rebuilding houses in the middle of nowhere! It’s funny, I feel like I spent so much time there complaining—about the heat, the work, getting up at the crack of dawn every day—but looking back on it I feel almost nostalgic. Like I actually really miss making dinner together every night, and even just talking to you. I feel like we had such good conversations! It’s been awhile since I met someone who I felt so comfortable talking to.

I hope your school year is off to a good start. How are your classes this semester? Did you get the LFV internship? I miss you and hope to hear from you soon (but also totally understand if you can’t write back right away because you’re busy!)

Love, Mia

The old man came to the signature with a sense of accomplishment, having read and understood the entirety of the English text. But he didn’t know what to feel after that. He hadn’t had any particular expectations for the letter’s content, so he wasn’t sure how it had contradicted them. He spent a long while sitting at the table, staring at the letter without rereading it, wondering how it ought to make him feel until he finally concluded that it really wasn’t meant to make him feel anything. It wasn’t for him, there was no coded message from the universe lurking between Mia’s looped Ys and tilting Ls. Whatever this correspondence meant to Ari and Mia, it had no relation to the old man besides the mistaken address. He refolded the letter, tucked it back into its envelope, and stowed it in the back of a desk drawer.

The old man was not actually that old. He only felt that way because his neighborhood was full of so many young people. Mirrors didn’t help, either; indeed, he looked as if he had crossed the threshold from middle- into late-age years ago—already, orange-brown age spots pocked his skin, already his hair had faded to a coarse gray and grew sparser, it seemed, by the day. Only his thick moustache recalled the vigorous man he had been in his youth, and even that was parenthesized by the deep creases folding from his nose to his rounded chin. Saggy sacs of flesh hung beneath his eyes like—he thought gloomily—little scrotums. His ears stuck out from the sides of his round face, small and gnarled and pink; his otherwise-modest nose ended in a large, flushed bulb. Barely five and a half decades had gone by since he’d emerged, a screaming red wriggly thing, from his mother’s womb, and yet his face appeared to have weathered a century.

His son still laughed when he called himself an old man, but soon, he suspected, it would be too true to be funny. Besides, he was already a grandfather—didn’t that automatically qualify him as old? “It is different here,” his son insisted, “In America, you are not old until 65. Then you retire and become old. You still work, so you are still young.”

The old man thought about arguing that his job could hardly be considered work; he spent four hours a week at the college up the road, conversing in Polish with the two or three students per semester who were preparing to study abroad in his homeland. Instead, he asked in Polish whether that meant that if he never retired, he would never be old. “I have found the secret to eternal life!” he declared, and his son laughed.

Their conversations often proceeded in such a manner, the son speaking English and the father replying in Polish. By now his son spoke English as easily as the language in which he had been raised. Though other Americans said that he still retained a vaguely Slavic accent, to the old man’s ears, his son’s English was perfect. His own progressed much more slowly—he suspected he was too old to learn a language, that his brain was no longer flexible enough to fold and bend itself around the complexities of a new tongue. He knew now that he should’ve begun his study when his son first traveled to the United States to attend university, though of course he hadn’t realized at the time that the move was a permanent emigration.

The old man’s first trip to the country in which he now resided had been to attend his son’s wedding. It had seemed only natural that his son’s letters from school included passages about a lovely American girlfriend, but still the phone call in which his son announced his engagement had come as a surprise (to him, at least. His wife, as it turned out, had long understood its inevitability). The trip had been filled with all the parental joys and anxieties of seeing a child married, in addition to the novelties and mishaps of foreign travel (he had been both intrigued and disappointed to discover that McDonald’s didn’t taste any better in the US), and his heart was only broken once, or rather continually, upon hearing his son’s name pronounced “Jay-cub,” or “Jake,” despite his having been christened “Jakub.” Not once during that trip did the old man realize, or even imagine, that it was his first visit to his future home. Though of course he hadn’t known how soon Warszawa would become a place of loss and loneliness.

It was easier to live without his wife in America, where there were fewer traces of her presence, where there were fewer memories of shared moments to haunt him through his daily routines. Home was family and his family was his son and his son’s home was America and so America was home now. He had left his grieving behind and resolved that from now on, when he thought of his wife, he would think of her life and not his loss. This, of course, was easier said than done, but as one season had rolled gradually into the next and his days had filled with routine distractions, the empty aches dulled and receded, and without noticing, he had grown accustomed to his new life.

He had completely forgotten about Mia’s letter by the time, a few weeks later, another one materialized in his mailbox. Clearly the misaddressed letter had not been a one-time error; she must have written her friend’s address down incorrectly when she received it. In the old man’s youth, such a mistake would’ve been tragic indeed, but nowadays you could find people easily on the computer if you needed to, and that was if you didn’t already have their phone number or email.

He only hesitated for about an hour or so before opening the letter this time—the amount of time it took him to realize that even though he sat with the newspaper open across his lap, he wasn’t really reading it. The handwriting was the same as before, though the ink was blue instead of black, the cheerful dips and loops sitting happily on the light-blue ladder rungs of the page’s lines.

Dear Ari,

Hi! How are you? I hope you don’t think I’m trying to be passive-aggressive or something by writing you another letter before you’ve replied to mine. I absolutely understand if you’re busy with school or work or social stuff or all of the above. I’ve just had some downtime this week, so I thought I’d use some of it to write to you!

My social life has been pretty dull this semester since my two closest friends are both abroad. I still go out on the weekends and spend time with other people, but I’m not meeting people for lunch and dinner every day like I used to. Even though I’m alone a lot, I don’t think I’m really “lonely,” at least not most of the time. Obviously you know I’m pretty introverted anyway, so I don’t mind being on my own a lot, and in fact, I’ve kind of come to enjoy going out to eat by myself. I like to bring a book to read while I wait for my food—I admit part of the reason I read instead of going on my phone is because I don’t want to seem like a stereotypical Instagram-addicted millennial, even though I basically am, and even though the only people who would judge me at a restaurant would be strangers so it doesn’t even matter.

It actually kind of bothers me how much I care about what other people think of me—I know logically that it’s not important how strangers judge me, yet I notice myself acting a certain way or doing certain things because of the way I want to be perceived. Do you ever feel the same way? You always seem so confident in yourself, like you know exactly who you are and you don’t care how you come off to other people because it doesn’t actually matter. I wish I could be that way. Could you teach me? Ha ha!

Not to be cheesy, but I’m really grateful that I had the chance to meet you and get to know you this summer. I mean that sincerely. I feel so comfortable talking to you (and writing to you) and it means a lot to have someone that I feel safe confiding in. So much of the time it feels like I should pretend I don’t have any insecurities, but I really liked what you said that one time about not being embarrassed about being embarrassed. I don’t know, it’s really stuck with me. You should write an advice column or something!

Anyway, I hope things aren’t too hectic and that I’ll get to hear from you soon! Miss you!

Love, Mia

As the old man refolded the letter and tucked it back into its envelope, he thought sheepishly that it was probably not entirely legal to read somebody else’s mail, even if it was delivered to your house. If it wasn’t illegal, then it was certainly unethical, and if it wasn’t unethical, then surely it was at least impolite. He wondered whether he ought to ask his son the next time he saw him, but he knew that in doing so, he would only be seeking vindication for an act that he already knew was wrong.

Instead, he pulled on his fleece jacket and stepped out into the brisk afternoon; after the warm sunshine of September, this was the first week that really felt like fall. The trees overhead were still saturated with summer green but underfoot, dry leaves crackled and acorn hats popped liked bursts of vapor in a burning log. The sky was a dusky violet when he rose in the morning and already fading into indigo by the time he sat down to dinner. The still air was calming in the absence of the rattling cicadas.

He walked north along his street, admiring as he passed, the prop-strewn lawns of his neighbors. Halloween was a bizarre and amusing tradition, he had learned last year, and he had since decided that it was his favorite American holiday besides Thanksgiving; already he looked forward to greeting the neighborhood children with sweets and chocolates, to seeing them scamper eagerly about in their playful disguises. This year, he’d been informed, his grandson would be going as a pirate.

He paused, as always, at the telephone pole on the corner, where people had stapled various posters and fliers, creating an unofficial neighborhood noticeboard. There were posters for two missing cats and one dog, and he did his best to commit their names and pictures to memory, just in case. There would be a yard sale down the street next weekend, and the high school football team was holding a fundraiser to raise money for breast cancer. A newly certified babysitter advertised her services beside a notice about the upcoming PTA-organized Fall Fair and the flier for the annual Halloween 5K and Fun Run (costumes strongly encouraged!). He took his time, reading all the details about each event, making sure he understood exactly what each entailed so that he felt fully informed on the goings-on of his neighborhood, even though he knew he wouldn’t attend any of them. Many seemed like they could be a good time, but the old man also knew that they weren’t intended for him.

He continued along his daily route, inhaling deeply the sharpened air that his mother had always told him made for a healthy constitution. Autumn crackled beneath his feet and he savored the red flush he knew was rising in his cheeks and nose and ears. His hands nestled warmly in his pockets as he navigated the streets that had gradually become familiar, until his daily walks no longer required navigating but merely strolling, meandering, enjoying the lovely weather as he made his way back to his house.

“What’d he say, Jake?” his son’s wife asked, and Jakub translated his father’s joke into English for her, and then she laughed, too.

“That’s very clever, Mikołaj,” she noted. Her pronunciation of his name was heavily accented. Still, at least her “Meeko-wee” was closer than most guesses he’d heard from Americans, ranging from “Micka-lash” to “Micko-lage” to “Meeko-ladge.”

“Mommy, I’m hungry,” whined the small boy playing at the woman’s feet.

“It’s not dinnertime yet, Ethan, you’ll have to wait,” his mother told him patiently.

The boy tugged at the hem of her pants. “But I’m hungry now.”

“I’m sorry to hear that, buddy, but you’ll just have to wait for dinner like the rest of us,” she said with a shrug.

“It will be at least an hour until we eat, Melissa,” Jakub said, checking his watch, “He can have a small snack.”

“Small,” Melissa repeated.

The child clapped eagerly as his father hoisted him off the floor, grinning and chanting, “Go-gurt! Go-gurt!”

“No,” Melissa called as Jakub carried their child into the kitchen, “Maybe some fruit.”

The departure of the child and, more significantly, Jakub, who was the primary conduit for conversation between his American wife and his Polish father, created a vacuum in the living room. The old man’s gaze drifted amiably from the decorative but unread coffee table books, to the squirrel attempting to climb the birdfeeder in the garden, and around to his daughter-in-law, who was chewing on the inside of her cheek and struggling to find somewhere to land her eyes. The silence appeared to fluster her, though Mikołaj didn’t mind it. Americans, it seemed to him, always felt uncomfortable in the absence of dialogue, or maybe it was just young people who couldn’t tolerate quiet. Eventually, unable to stand it any longer, Melissa said, “Well, I hope you like baked ziti!”

“Yes,” he replied, “very good.”

“I’m also making garlic bread, and some steamed vegetables—broccoli, green beans, you know.”

“Very good,” he told her, nodding enthusiastically because he didn’t have the English words to say, That sounds wonderful; I’ve enjoyed everything you’ve cooked before and I’m certain tonight’s meal will be just as excellent. She always seemed unsure around him, anxious to please. He suspected that it was because he couldn’t properly express his gratitude or affection for her, so she had no way of knowing that she had nothing to be anxious about.

“You know,” she said, after another pause, “it would be wonderful to have some traditional Polish food. Jakub tells me about all the delicious things he ate growing up—pierogies and kielbasa, babka, chrusciki…” He found her attempt at the Polish pronunciations endearing, and yet she still said her husband’s name as if he were an American.

He smiled and shook his head, “My wife, was cook. Very good. I am not good.”

“Oh,” Melissa replied with half a laugh, “I guess that’s how it usually is over there, isn’t it?” The old man shrugged. Yes, in Poland it was typical for women to do most of the cooking, though from what Mikołaj could tell, this was the same in America. His wife had often scolded him for being so helpless in the kitchen, teasing that he wouldn’t have been able to make a palatable borscht even if Jesus Christ himself were coming to dinner. Mikołaj had laughingly returned that if the Good Shepherd ever found himself under their roof, surely they would think of something better to serve Him than borscht.

Silence descended once more, and after a minute or two, Melissa took a breath and rose from her chair. “Well,” she said, slapping her thighs, “I’m going to start getting dinner together. Do you need anything? Anything to drink?”

“No,” he replied, “Thank you.” She smiled at him and escaped into the next room, rescued from his awkward company by the promise of a chore. The old man remained behind, seated comfortably in the La-Z-Boy armchair that had been unofficially designated his. He could hear the voices in the kitchen but did not strain himself to understand them, instead unfolding the letter that he had found on his doorstep as he’d left his house that afternoon.

Dear Ari, the letter read,

I’m beginning to suspect that you’re not receiving my letters—but also please don’t be offended if you are and just haven’t had the chance to write back yet! Feel free to text or call or email me if that would be easier; I just like writing letters because it feels so quaint, and also somewhat…intimate, I don’t know. And also I’ve never been confident enough to say what I really think out loud, it’s so much easier to write it out on paper.

I actually wanted to write to you because I received some bad news a couple days ago and honestly I don’t really know what else to do about it. My dog ran away. I’m sad, but I’m also really angry, like I can’t help blaming my family for letting it happen, for losing her. It’s not like she consciously decided to go on some grand escape, someone must’ve accidentally left the fence unlocked or something, so obviously it’s somebody’s fault. I want to be sad that she’s gone, but it sucks because there’s still a chance they could find her, you know? And of course chances are she’s probably dead, but I’m so angry because we don’t know, and probably never will, and I never got to say good-bye and I feel like there’s no way to have any closure.

I feel kind of stupid for being so upset about my dog, like I can’t help thinking I’m overreacting. Sure, it’s hard to lose a pet, but so many people have to deal with so many worse things, and what right do I have to be sad about this? Sorry for being so angsty. It’s kind of shitty of me to be unloading on you, but also, I don’t really think you’re reading this. I don’t know what’s happening to my letters, maybe a raccoon is stealing them out of the mailbox before the mailman picks them up. Maybe they’re just disappearing into the postal service, and I’ll probably never know what’s happening to them and I’ll never have any kind of closure about it because there are no fucking answers when things just get lost. Sorry for being angry. I’m sure I’ll be over it in a week or so. I’ll write you again when I’m in a better mood.

Love, Mia

Mikołaj had never had a pet. He’d gotten Jakub a goldfish once, after the child had spent weeks begging for a puppy; he’d told his son that if he could prove himself responsible enough to look after a fish, maybe they could consider a dog. As predicted, the boy had lost interest after a couple of weeks. Mikołaj had flushed it down the toilet when it had inevitably died from neglect.

He hadn’t felt anything in particular while reading either of Mia’s previous letters, but now Mikołaj felt a self-conscious sympathy stirring somewhere behind his sternum, not because the girl had lost her beloved pet but because she felt the need to apologize for being upset about it. He spent several minutes composing the inspirational speech he would give Mia when, during the middle of their conversation, she would apologize to him for telling him about her unhappiness. But then the old man reminded himself that he would never meet Mia and she would never apologize to him for telling him about her unhappiness and even if she did, she wouldn’t understand his speech because the entire thing was in Polish.

Jakub and Ethan eventually rejoined the old man in the living room and he hastily tucked the letter back into his pocket. Ethan quickly became engrossed in his plastic firetruck, allowing Mikołaj and his son to converse comfortably in their native tongue. Jakub complained convivially about his boss, whom he secretly admired and respected but pretended to resent because (his father suspected) American television implied that he ought to. Mikołaj relayed the latest episode of his ongoing attempt to befriend the Ukrainian woman who worked at the convenience store by his house. He was regaling his son with the details of their conversation this morning (“How much?” “Four dollar.”) when the child suddenly looked up from his toy and asked, “Daddy, why do you talk funny with Jha-jha?”

“It’s called Polish,” Jakub explained patiently, as he had numerous times before. “It’s easier for Jha-jha to talk Polish than English.”

“Why?”

“Jha-jha lived in Poland for a very long time before he came here. He’s not used to talking English yet.”

“What’s English?”

“English is what we are talking now.”

“I can teach Jha-jha to talk English!” Ethan exclaimed.

Both adults laughed. “Yes, very good,” the old man agreed. Maybe, he thought, when the boy grew older, he would teach him Polish. Frankly, he was surprised—and perhaps a little disappointed—that the child wasn’t being raised bilingual; “Jha-jha” was the closest the boy could come to his paternal tongue, a child’s distortion of dziadek, grandfather. Mikołaj had asked his son about the choice to only teach Ethan English, and he’d replied that trying to learn two languages at once would be too confusing, that it was more important for him to know English so he could talk to his friends at daycare. Ethan was American, the idea went, not Polish-American. By this logic, Mikołaj reasoned, it was not Ethan’s responsibility to know Polish, nor his father’s duty to teach it to him, and thus, Mikołaj was the only one who could possibly be at fault for his inability to communicate with his grandson, or with his daughter-in-law for that matter. He was to blame for the uncomfortable silences, for the misunderstandings and mispronunciations. It was his own fault that he couldn’t take part in the conversation shared over Melissa’s casserole, that he lost focus as their English grew more rapid and colloquial, that he was relegated to a vaguely-smiling silence he’d earned himself by being a poorer conversationalist than his three-year-old grandson.

Dear Ari, Mia wrote him, for the routine arrival of her letters had convinced Mikołaj that he was indeed her correspondent, that she intended for him to read them,

I’m sorry about that last letter. I was frustrated and needed to vent, and I don’t think it had sunk in at that point that Cedar is really gone.

I wish you were here. I think it’s kind of mean of the universe to have let me meet you and get to know you and then have you go to college on the other side of the country. Wanna transfer? Just kidding, of course. I know you have your own life out there, your own problems, your own friends… I don’t understand how people in long-distance relationships can tolerate it.

Mostly I think I’m homesick again, or not quite homesick…more like family-sick. I realized a few days ago that I haven’t really hugged anyone since my parents dropped me off in August, and that I probably won’t hug anyone again until I’m home for Thanksgiving. It’s less than a month away but that feels so long from where I’m standing now. I wish you were here so you could hug me; hugging you really helped when I was homesick in Oklahoma. I don’t know, you’re just a really good hugger. Not to be weird about it. But I’ve reached the conclusion that you’re not getting these letters anyway and if you are, there’s a reason you’re not responding so it doesn’t matter.

I never said this to you, and wouldn’t tell you in person, and wouldn’t even write it if I thought you would actually read it at some point, but I really like you. As more than a friend. I’ve known I liked girls for a long time but you’re the first one that I’ve ever really had a crush on, that I can really see myself in a relationship with. I just felt so safe and comfortable and happy around you, and even though we’ve only known each other a couple months, I absolutely trust you and just want to be with you, to have you here with me. And I know it’s pointless because you have a boyfriend and are happy and I feel like you probably see me as kind of childlike and inexperienced, but I just wanted to tell you that that’s how I feel, how I’ve felt since we were in Oklahoma together.

I realized it that night we were sitting out on the porch in the thunderstorm, just sitting together watching and listening to the storm and not saying anything but just being there, in each other’s presence. I realized it so suddenly that I almost wanted to cry. It’s been a long time since I’ve felt this way about anyone, but I didn’t want to make things pointlessly awkward by telling you since there was no chance anyway. I’m only telling you now because, like I said, I know you’re not reading it, and I figure the chances are I’ll probably never see you again anyway, so what the hell?

I hope things are going well for you and that whatever you are doing and whoever you are with makes you happy. I mean that sincerely.

Love, Mia

When he began to realize what Mia was saying, Mikołaj forced himself to focus on each individual word, second-guessing his understanding of each, double checking in his Polish-English dictionary, deciphering it line by line like an archaeologist translating an ancient tablet; the meaning didn’t matter, only the translation, the words, the hollow casks of language. By the end, he had read the letter and understood all the words and had tried not to allow himself to connect the words to the ideas they conveyed. He knew what it meant, he knew to what Mia was confessing; he felt it inside him, like algae in the walls of his intestines. He pushed the letter deep into his pants pocket without refolding it and walked out into the descending evening without locking the door behind him.

Normally his walking routes meandered through the neighborhood, but now he simply walked straight, too preoccupied to pay attention to street signs or turns. He’d known it was wrong to open those letters, he thought angrily as he kicked dead leaves along the brick-work sidewalk, he’d known it and he had done it anyway, stupidly assuming that there were no consequences, no risks.

His straight-line route carried him to the main street running through the campus where he worked part-time. Ordinarily he disregarded the strangeness of the students—the metal hoops dangling from their noses, hair cut jagged and dyed in outrageous hues, bellies and cleavage and thighs blithely exposed by outfits that did not seem to Mikołaj to have any kind of cohesion. He’d dismissed these things—students were students and students were young and young people did silly things—and focused instead on correcting their verb order and helping them pronounce new vocabulary.

Now he saw anew the same students he’d walked past daily for the last two years. These young people treated their bodies irreverently, disregarded the principles of decency in favor of superficial wildness. He tended not to think about what they did with the 166 hours of the week during which they were not with him; he didn’t want to probe that aspect of their lives. There were things he’d known he didn’t want to know and he’d been foolish to think they would not appear in the letters he’d unwittingly intercepted.

He scuffed his shoes against the slate-paved campus walkways. The letter crunched in the crease of his hip with each step. Mia’s words, innocent and sinful. The old man did not understand exactly what it was they were making him feel—he was angry at her, he was sad for her, he was sickened by her, he was worried about her. About someone he had never met! Someone he’d never even seen, knew only as handwritten words in a language that he barely understood. He was almost sure now that this revelation was the punishment for his crime, but whether his crime was in reading the misbegotten letters or in beginning to care for their writer he did not know.

Eventually the sun crept below the treeline and the air’s crispness turned to a sharp chill that cut at the old man even through his jacket. Soon he would have to dig his heavy wool coat from the back of the closet where he’d buried it last April. He turned towards home, surprised again by his yearly surprise that autumn was not simply autumn but a warning of winter.

He wanted to ask his son to read the letter before he sent it, to weed out the misspellings and false constructions that he himself was incapable of finding. Even the few simple sentences, he was sure, would reveal his ineptness with the English language, but even more embarrassing than the inevitable errors in his prose would be explaining to his son the reason he had written the letter in the first place.

It was simple, more a note than a letter, really:

Dear Mia,

I am sorry. Your letters to Ari comed to my house on mistake. I was lonely and I read them despite it is wrong. I am very sorry. Here are back your letters.

From, Mikołaj

He copied the return address from the leftover envelopes onto a fresh one, and filled in his own name above the address Mia had thought belonged to Ari. He folded her handwritten pages and slid them in behind his own note, then blotted his tongue along the sticky-dry strip of the envelope’s seal; the papery-sour taste of it lingered in the roof of his mouth as he placed it in his mailbox and flipped up the little plastic red flag.

At first he did not know whether he wanted her to write back. As the unanswering weeks went by, though, he found himself hunting through the bills and the advertisements for her handwriting, expect-want-hoping for a frightened reprimand about his invasion of her privacy, a gentle acceptance of his apology, an angry threat to tell the police, but none came.

Winter came, though, with the first feeble snowfall in the first week of December; the semester drew to a close and he said his last pożegnanies to the students who would depart for Warsaw in January only to be replaced by a new batch preparing for the journey the following fall. Jakub came by to help his father shovel his driveway, though the old man insisted he was not so old as to need such help. He bought a wreath from a Boy Scout who lived up the street to hang on the front door.

The prospect of hearing from Mia withered with the grass beneath the snow, and Mikołaj’s thoughts returned to his wife, lying cold and alone under the snow an ocean and half a continent away. Beside her was an empty plot, once reserved for him, which he knew would never be filled. He had forsaken her. He had left her behind in eternal isolation, as if he had not known that he belonged beside her, as if he had actually believed that he could ever find a home anywhere besides that vacant plot of earth.