If you fly over Jackson Heights on approach to LaGuardia airport, the neighborhood appears as a cluster of leafy blocks pierced by dozens of brick apartment buildings. And if you had happened to fly over on one particular summer afternoon, with binoculars and exceptional eyesight, you just might have witnessed what appeared to be me trying to dump my wheelchair-bound mother into oncoming traffic.

I wasn’t really trying to kill my 89-year-old momma, of course. This was the first day that I’d taken her out of the nursing home where she’d just arrived, and I was still learning how perilous New York City sidewalks could be. That’s the kind of thing you don’t really notice until you’re pushing someone in a wheelchair.

I’d started out with the best of intentions. A nasty brain tumor was taking an increasing toll on my mother’s memory, so I thought that seeing the neighborhood might help her to better grasp the recent changes in her living situation. Seeing first-hand how close my husband Angel and I lived might provide some comfort, too.

I followed the official protocol for leaving with a nursing-home resident, signing a form at the second-floor nurse’s station and then another at the lobby reception desk, accepting full responsibility for my mother’s wellbeing while we were gone. Then the sliding glass doors parted and suddenly we were free. The sun and the warm breeze caressed my mother’s face for the first time since her arrival in the Big Apple a couple days earlier. She smiled.

“Isn’t it a beautiful day, Momma?” I said, patting her bony shoulder as I gazed at the green leaves swaying above us.

She wrapped her slender hand around mine. “Yes, it is. We’re having a big time,” she said, the last two words mimicking the Kentucky accent and terminology of her youth.

I felt a rush of optimism as we moved further from the somber brick building, past manicured shrubs and vibrant flowerbeds. We’d make the best of this new reality. Taking her out today was proof that I could integrate my mother into my life. Angel and I would invite her to dinners at our apartment. I could take her on errands and maybe even to visit nearby friends. Why not?

Life won’t be so bad for her, I assured myself as I pushed the wheelchair along the wide gray sidewalk, along cracks that seemed designed to be speed bumps. I was flying high on my positive thoughts — and perhaps congratulating myself a bit on being such a wonderful son — as we descended a small ramped area to cross the street. Then, WHAM. The front wheels ran straight into a sizeable bump where the sidewalk met the pavement. The chair slammed forward. My mother grabbed both armrests and pushed her feet against the pedals, using what must have been a tremendous amount of strength to stay in place as I labored to lift and return the wheelchair to a more upright position. Thanks to her — not me — she didn’t fall into any traffic.

I didn’t realize there’d be bumps in the road.

“Oh my gosh, Momma, I’m so sorry,” I said, pulling her back against the chair. “Are you OK?”

“I’m fine,” she laughed, her eyes sparkling behind tinted glasses as her good hand smoothed her short gray hair. “This just adds to the excitement of being outdoors.”

“I hope you’re not going to tell the people at Regal Heights that your abusive son is trying to murder you by pushing you into traffic.”

“Oh, and you’ll get so much money if you do kill me!” I could see the smile curling around her face as we continued our turbulent ride across the street and into Alex’s Pizza Deli. She didn’t have much of an appetite since arriving in New York City, but she humored me by eating one greasy, envelope-thin slice, accompanied by half a bottle of Coca-Cola, her all-time favorite beverage.

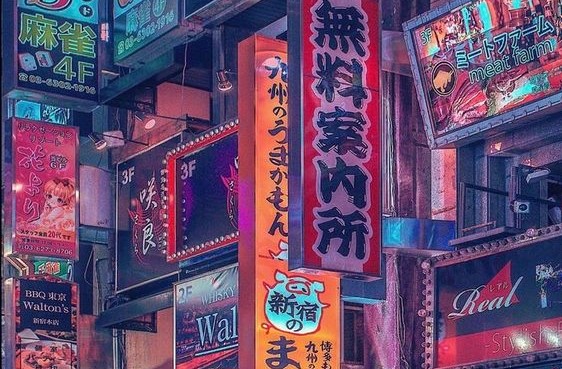

After lunch, we continued our precarious journey along the pockmarked sidewalks, the aroma of south Asian produce tickling our noses as we passed Mina Bazaar — just one example of the neighborhood’s incredible diversity.

“It’s very pretty around here,” my mother said, her hands tightly grasping the armrests, probably in case I decided to dump her again. “Tell me again what this area is called?”

“It’s Jackson Heights, it’s a historic area in the borough of Queens, in New York City. Angel and I live here too, just a few blocks away.” I didn’t bother going into detail about a company called the Queensboro Corporation that developed this entire district in the early 20th century, building six-story complexes that they dubbed “garden apartments” to attract middle-class and upper-middle-class New Yorkers looking for more space. My husband Angel and I bought a place here in 2002, when we realized that our money went further in this 36-block landmarked district than anywhere in Manhattan (and most of Brooklyn). In the 21st century, Jackson Heights has become one of the world’s most internationally diverse neighborhoods, as well as the gayest area in New York City outside of Manhattan. Its shady streets and lovely architecture made for pleasant strolling; I just needed to get the hang of doing it with a wheelchair.

I leaned forward as the sidewalk angled steeper. Just as I was reaching the top of the block, my right leg vibrated. We stopped under the shade of a giant tree, not far from the gaze of a pair of stone griffins that adorned a nearby apartment building entrance. I pulled out my cell phone.

“Mr. Chesnut? This is Allstate calling you back regarding Eunice Chesnut’s account,” the voice said.

This was one of several calls I’d gotten regarding my mother’s accounts. My chipper mood immediately turned apprehensive. My mother had a lot of legal and financial issues that required our attention — change of address notifications, bank account closings and insurance policy cancellations. But she was quickly losing her memory.

I should have known there’d be bumps in the road.

In some ways, my mother had planned well for this day. A couple years earlier, she placed my sister’s and my names on her bank accounts, making it easy for me to write monthly checks from her account to pay the nursing home bill. Together, we were overseeing a shrinking estate that was never that big in the first place. She paid about $3,000 a month out of her own pocket to live at the assisted living facility in Brockport, and was now forking out over $10,000 at Regal Heights. We were in a draining situation called a “spend down,” which required my mother to exhaust nearly all of her savings in order for Medicaid to kick in and pay her nursing home bills. Given her meager savings, it wouldn’t take long to reach that point.

Meanwhile, we had to make a lot of changes. Whether it was a bank or an insurance company, the telephone protocol was always the same. I’d need to put my mother on the line so that she could confirm personal details and authorize the representative to speak with me.

She had a brain tumor, not Alzheimer’s or dementia, but the effects were similar. It felt like I was racing against the clock of my mother’s fading alertness to wrap everything up.

At what point would she no longer be able to recite her name, social security number, birthdate? What happens if she can’t confirm her own identity? Should I just pretend to be her, imitating that nasal midwestern accent paired with a few southern inflections? I used to mimic her speech patterns right to her face, just to be obnoxious, when I was a teenager. How is some random insurance agent going to know that it’s not her?

I decided to be honest, handing the phone over to her.

“Momma, it’s your insurance company calling. Remember how we need to change your address since you moved? They just want you to answer some questions and say that it’s OK for them to speak with me about your account.”

“OK, so what do I need to tell them?” She hesitated before taking the phone. “You know I can’t remember anything anymore.”

“Don’t worry,” I said, masking my concern. “It’s just the basic stuff like your name, birthdate and social security number.”

Her skinny hand twisted awkwardly around my iPhone as if she were trying to reach around the corner of a building. “Hello?” She turned to me. “I can’t hear anything, sweetie.”

I moved the phone closer to her ear. Suddenly the humid summer air felt uncomfortable.

My mother frowned while listening. “Yes, this is she,” she said. “November 6, 1925.” Then she slowly recited her social security number. “Yes, that’s fine, my son will talk to you about all of that. I give you my permission. Thank you, you too.”

I breathed a sigh of relief as I took the phone and finished the call. My mother sat quietly, watching passersby. After 10 minutes, we were done. “I’m sorry that took so long, Momma. Since it’s so hard to get people on the phone, I didn’t want to miss that call, even though we’re standing outside.”

“It’s OK sweetie. Now who was it again that you were talking to?”

“It was the insurance company. They just needed some more information to change your address.”

“Oh, well, that’s good. I appreciate you taking care of that.”

“I couldn’t do it without you, Miss Eunice. So … now that we’re done with all that boring stuff, would you be interested in rolling over to see where Angel and I live? It’s just a couple blocks from here.”

She looked in the direction that I was pointing and pursed her lips. “Actually, sweetie, I think I might like to go back home now. I’m kind of tired.”

Angel and I had worked with my sister, Glynn, to warm up the cold institutional ambiance of my mother’s room at the nursing home, but with limited success. We hung up a print of the Morgan-Manning House, the Victorian-era mansion where my mother had served as historian for more than 30 years. We plopped framed family photos on her nightstand and dresser. We connected the television and phone. We set up folding chairs, so all of us could sit around her bed at the same time.

But the framed print kept sliding off the wall. The photos on the table kept toppling over. My mother couldn’t hear the phone ringing and didn’t remember how to answer it, or even speak into it if we handed her the receiver. And a nurse informed us that extra seats weren’t allowed in the room, because they might block access to the bed. I took the chairs back to my storage unit and disconnected the phone.

It didn’t really matter, I guess. My mother didn’t seem to notice anything missing, and when we returned from our outing we simply stared at some TV talk show while we chatted. After a few minutes, a well-dressed woman with sand-colored hair and glasses entered and introduced herself as Connie, the nursing home’s social worker. She turned to my mother.

“If it wouldn’t be too much trouble, would you mind if I steal your son for a little while, Mrs. Chesnut? Then we’ll both come back and see you, too.”

“Fine, fine,” my mother smiled.

I followed Connie to her small office on the first floor. Taking a seat at her cluttered desk, I learned that our impromptu meeting was about a topic that I thought was already taken care of. Years earlier, my mother had filled out a pile of end-of-life paperwork, forms with important titles like Do Not Resuscitate, Living Will and Power of Attorney. Her main directive to us, for the past couple of decades, had remained clear: no life support. Pull the plug. She’d already visited enough elderly friends in hospitals and nursing homes to realize she didn’t want to pointlessly extend her life.

“I understand that your mother has already completed the forms,” Connie acknowledged with a formulaic smile. “But we need to have new ones signed to indicate exactly what this facility can and can’t do for her, in the event of any specific circumstances that might occur.” She handed me a sheet with a surprisingly long list of “what ifs” (pleasantries such as “patient is unable to eat,” “patient is unable to breathe”), each of which required a separate answer. The form also asked me to choose whether or not my mother wanted a “natural death.”

“That means the staff would let nature take its course,” Connie explained. They wouldn’t step in with life-sustaining drugs or treatment. Natural death was exactly what my mother wanted, especially now, so I quickly checked that box.

It was dinner time when we completed all the paperwork, so Connie accompanied me to the second-floor cafeteria, where dishes clanged from the kitchen and my mother was picking at the remains of a nearly empty food tray.

“Hello Mrs. Chesnut,” Connie called out as she moved the tray to a nearby table and set the pile of forms in front of my mother. She launched into what was almost a word-by-word repeat performance of the explanations she’d just given me. But I must give Connie credit. This time, she said everything slower and louder, carefully pronouncing every word, which was the best way to assure that my mother could hear and understand.

“Does all of this sound OK, Mrs. Chesnut? Do you have any questions?”

“If Mark says it’s OK then it’s OK,” she said, pen in hand. “Now where do I sign?”

“Right there, where my finger is,” Connie pointed.

Slowly and deliberately, my mother moved her bandaged hand near the paper, but the fingers holding the pen were nowhere near the signature line. She moved it again. Still way off. It was like one of those arcade games, where you can never quite maneuver the robot arm to the right place in order to grab the prize.

I pointed too, as if my finger would somehow be more effective than Connie’s. “Right there, Momma, can you see the line?”

“I’m trying.”

Another move, even further from the line. I couldn’t tell if her inability to sign was because of cataracts, the bandaged hand or general confusion.

Of course there are bumps in the road.

“That’s OK, Mrs. Chesnut,” the social worker interrupted. “You can just sign anywhere on the page.”

Finally, the pen reached the paper, and a vague autograph appeared. It was not the signature of the woman who’d raised me. But it was OK. Sometimes you just have to deal with the bumps and keep moving forward.